The Rise and Fall of Caligula: Rome’s Most Controversial Emperor

From Beloved 'Little Boot' to Tyrant: How Trauma, Power, and Illness Shaped Caligula’s Tumultuous Reign

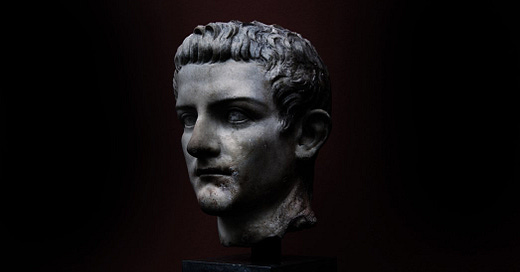

The Subject

You may not be familiar with the name ‘Caligula’, but you definitely know his family, the Caesars. The family dynasty began with Julius Caesar, a Roman politician and general who ruled as dictator before being stabbed to death by a number of friends turned assassins (most notably Brutus, as we were all taught by Gretchen Wieners).

The murder of Julius fueled the fires of civil war in Rome, with his great-nephew/adoptive son Octavian taking up his mantle and squaring off against Marc Antony for power (this is the Marc Antony who killed himself upon incorrectly learning that his lover Cleopatra had died while fleeing Octavian’s invasion). Octavian was the last man standing and became the first Roman emperor, taking the name Augustus. Caligula, our subject, was Augustus’ great-grandson.

An important note for making sense of the family trees during this period: it was a common practice for Roman men, including emperors, to adopt male relatives as their “son” and heir. Unlike the monarchies we have explored up to this point, an heir didn’t have to be the legitimate son of the ruler, or really even blood related, as long as he was legally recognized as such. Hence how Octavian/Augustus was the great-nephew AND adopted son of Julius Caesar.

Caligula, or Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus, lived a life in the spotlight from the moment he was born. He was given the nickname “Caligula”, which means “little boot”, by the soldiers his father commanded because of the cute little uniform he would wear. For the first years of his life, he lived with his parents at military camps and traveled with his father Germanicus on official business. Germanicus was the nephew and adopted son of the then-emperor Tiberius, and was greatly loved by his soldiers and the people of Rome. He was respected not only because of his impressive heritage, but also for his fairness as a leader and for his military genius. It was widely understood that when Tiberius died, Germanicus would take the throne.

Unfortunately, Germanicus’s life was cut short when he died at the age of 33. His family believed he was poisoned at the behest (or at the very least, the encouragement) of his adopted father, Emperor Tiberius, who had become jealous of his popularity. Caligula’s mother and brothers also died as a result of Tiberius’s jealousy; however, Tiberius chose to keep Caligula alive and under his watchful eye as a possible heir. After all, he was family and the boy's father was greatly loved even in death.

Although Caligula was undoubtedly grateful to be alive, growing up in Tiberius’s court of debauchery was not the ideal situation for any teenager. Tiberius’s vices included orgies and young boys, and ‘all indications point[ed] to Caligula being sickened by this lifestyle. [However Caligula] learned that, to survive, he must always be agreeable to whatever Tiberius wanted” (Dando-Collins). And apparently what Tiberius wanted was for his son/nephew to partake. Caligula lived in constant fear for his life, never knowing if Tiberius’ regularly changing mood would convince the emperor that Caligula was too much of a threat to keep alive. Then when Caligula was 24, Tiberius died (He was very possibly murdered. Sensing a theme here?). And just like that, “little boot” was the leader of the most powerful empire in the world.

For the first six months of Caligula’s rule, all signs pointed to a bright future for the son of the beloved Germanicus. He came out of the gates hot with a series of popular policies; he got rid of a law that made it easy to charge someone with treason on bogus grounds (this had happened to his mother and brothers); he made it legal to read books that the previous two emperors had banned; and he added an extra day to the Saturnalia festival (what would eventually evolve into what we know as our Christmas holiday). It didn’t stop there. “Caligula restored democratic electoral procedures….[and] he also made it possible for more commoners to advance to the Equestrian Order (an aristocratic class), improved the legal system, and over-hauled the tax system” (Dando-Collins). Fun fact: One of the prisoners pardoned as a result of Caligula’s popular measures was Pontius Pilate. Yes, that Pontius Pilate. The one who handed Jesus Christ over to the crowds for crucifixion.

Then, seemingly overnight, Rome found itself led by a very different man. Caligula fell ill in October of A.D. 37 as a result of an epidemic that swept across the empire. When he recovered weeks later, the historians of the time recorded that the emperor was no longer the optimistic and enthusiastic leader who was so eager to use his power for good. He was mean, with a short temper and an inflated ego. Caligula began to suffer from extreme insomnia and “never managed more than three hours sleep in any one night” (Barrett). He took a series of wives after forcing their husbands to divorce them, only to divorce them himself after a matter of days or weeks. And then, the changes to his personality began to impact his decision making as emperor.

Caligula set his sights on a prize that could cement his legacy: Britain. He marched his tens of thousands of his forces to what was mostly likely the shores of France. Then, he suddenly abandoned his plans for invasion, ordering his soldiers to collect seashells instead. Understandably, historians like Seutonius have pointed to this incident as one of the examples of Caligula’s mental instability.

As Caligula was pursuing military glory, he was also seeking praise of a higher order: religious. After declaring himself to be a god, Caligula attempted to spread his new religious order throughout his empire “so the world could worship him” (Dando-Collins). He ordered a massive statue of himself to be built and installed in the Temple of Jerusalem, causing outrage among the Jewish population. This was seen as a huge slap in the face, “desecrating the symbolic center of the Jewish Diaspora” (Misano) and stoking the fires of anti-semitism throughout Rome.

As Emperor, Caligula was an absolute ruler backed by the force of the Roman military and paid foreign soldiers. However, there was also a Senate body made up of non-elected rich and powerful members of society who acted as legislative advisors. And they were not pleased with the new Caligula. Not only were they confused by his legislative decisions (in a complete 180, Caligula reinstated the previously mentioned treason law and introduced new taxes), they were growing tired of Caligula’s dark humor and cruelty against members of their rank. At one point the emperor had threatened to make his favorite horse a consul, which were the highest elected officiala in Rome and were tasked with appointing members of the Senate. The Senate was not amused. Caligula had also made a habit of randomly arresting wealthy members of society so that he could confiscate their assets for himself. He also took advantage of one of the most barbaric practices common during this time: forced suicides. Instead of executing someone for their crimes, elite members of society were often given the honorable choice to take their own life - and Caligula made use of this with special cruelty following his illness. Caligula had adopted his cousin, Gemellus, when he took the throne and now ordered him to death (it's unclear if Gemellus was actually guilty of anything, or if the emperor was just paranoid that he was gunning for the throne). In addition to Gemellus, the man responsible for helping Caligula to the throne, Macro, also met the same unfortunate fate. Again, it was not the fashion in which Caligula ordered these deaths that brought concern, but the fact that these two men had once been considered close allies of the emperor.

As a result of Caligula’s increasingly erratic behavior, multiple plots to eliminate him began to form. The first involved his sisters. There are several ancient historians who claim that Caligula had an incestuous relationship with his sisters, but this was never proven and could very well have been a product of gossip aimed at tarnishing Caligula’s reputation. Caligula did have an extremely close bond with his sister Julia Drusilla. When she died at the age of 21 he was devastated and had Julia Drusilla declared a goddess, with temples and religious orders dedicated to worshipping her. But Julia Drusillas’s windower decided to team up with his surviving sisters, Agrippina and Julia Livilla, to overthrow Caligula. The plot was discovered and the sisters were banished to separate islands, where they stayed for the remainder of their brother’s life.

Where Caligula’s sisters failed, the Senate was successful. Rome was no stranger to the murder and assassination of important figures, but several times the co-conspirators lost their nerve and plans were abandoned. Finally, the opportunity presented itself during a week-long festival in the city. The Senators knew Caligula would be enjoying the theater performances. On the last day of the celebrations as he was leaving for a lunch break, he was ambushed in a tunnel and stabbed to death. Chaos ensued as the guilty men tricked Caligula’s guards into believing the murderers had fled, and a manhunt began to find the culprits.

While the wild goose chase was unfolding, government leaders turned their attention to the immediate future and what was to become of their empire with no ruler. The Senate wanted to revert back to the days when Rome was a true republic, afraid of being at the mercy of another emperor. Looking to eliminate anyone who could be a threat to this vision, they decided that Caligula’s wife and infant daughter were too much of a threat to leave alive. They were both brutally murdered. Meanwhile, the foreign soldiers in Rome who were historically paid by the emperor were now out of a job unless they could find a new master. They decided that the lucky (but reluctant) man would be Caligula’s Uncle Claudius (brother of his father, Germanicus). The soldiers declared Claudius Emperor of Rome and the Senators, who were greatly outnumbered, were forced to accept.

Caligual’s reign was brief and lasted less than four years, but that was all it took for the Roman elite to decide they had had enough of him. “Little boot”, the boy who had been so loved in his father’s military camp, became the first Roman Emperor to be assassinated. Before we look at the lasting impact of his four years on the throne, let’s consider what caused the dramatic change in Caligula that led to his downfall.

The Science

Caligula was a traumatized child, exposed to extreme depravity, and shaped by the assassinations of his family members. Caligula was an egotistical tyrant, a debaucherous psychopath, a frivolous fool. He was insane. He was immoral. He was a victim. He was a villain.

Who was the real Caligula? Our historical sources on this controversial figure are limited. Of the authors that wrote about him, none were alive during his reign, and all were potentially biased by political interests. It’s hard to determine if the “little boot” was scarred by a traumatic childhood, afflicted by a mental illness, or simply an evil emperor.

The medicald have information we have about him seems murky as well. Proposed diagnoses have run the gamut of alcoholism, bipolar, depression, temporal lobe epilepsy, dementia, encephalitis, and syphilis. But the case of Caligula illustrates an important point about mental and neurological diseases: it’s rarely just one thing. The case of Caligula isn’t as clear cut as one would like. He is the traumatized child; he is the mentally afflicted young man; he is the self-centered ruler.

Some academics suggest that Caligula’s behavior as emperor can be explained by the psychological effects of his early life experiences (i.e. losing his parents and brother, and then being sexually abused by the person responsible for their loss). Psychological and neuroscientific literature are filled with studies investigating the long-term effects of childhood stress. In fact, trauma is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.” The murders of Caligula’s family members and his forced participation in orgies seem to fit the bill.

As you can imagine, experiencing serious and chronic stress while your brain is still developing can have lasting consequences. It has been observed that children who experience trauma are more likely to go on to have mental health issues, such as addiction, PTSD, or depression. Childhood stress can also alter brain development, the immune response, and cognitive abilities.

One popular animal model used to study childhood trauma is the maternal separation stress paradigm. Researchers use this as a developmental rodent model of mood disorders, including anxious behaviors and increased alcohol consumption (yes, mice have been known to throw back a drink or two). Not only does this separation deprive pups of tactile and auditory cues from their mom that are important for development, it also activates the neuro-endocrine (hormone) stress response. It is the release of stress hormones that is believed to mediate the long-term effects of childhood trauma.

Interestingly, the effects of this model depend on the duration of maternal separation as well as the age and sex of the mice used. A 2010 paper from researchers at the Universidad Autónoma de Puebla in Mexico isolated newborn male mouse pups from their mothers for two hours per day for the first 12 days of their lives. The researchers later looked at three different brain regions involved in mood disorders in these mice before and after they went through puberty. They were particularly interested in looking at the structure of neuronal dendrites, which are the part of the cell that make connections with other cells and receive information. They measured three different aspects of dendrites: the number of dendrites within a region, the length of the dendrites, or how structurally complex they are. The researchers found that maternally separated pups had shorter, fewer, or less structurally complex dendrites in all three regions. These changes imply altered signaling in these regions, which could potentially contribute to mood changes. Importantly, these differences in stressed versus unstressed pups were worse after puberty than before it.

If we think about these data in terms of Caligula’s experiences, we can understand that his tumultuous childhood likely could have had biological consequences. Moreover, it’s not improbable that these effects would not have manifested themselves until he was a young adult. As you might remember from our Charles VI post, this is a particularly common time for young men to develop mental illness. Therefore, the idea that Caligula was shaped by his trauma and that he was also mentally ill are not in conflict.

In addition to his childhood increasing the likelihood of Caligula developing a mental disorder, his genetics also may have put him at risk. A 2017 paper analyzed historical records of the men in Caligula’s family and proposed potential mental illnesses and neurological diseases that might have afflicted them. Their final list included Parkinsonism, migraine, dementia, learning disorders, alcoholism, and depression. Intriguingly, of the 12 men they investigated, they found evidence for epilepsy in over half of them.

Epilepsy is a group of disorders characterized by seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of electrical activity in the brain caused by an imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory communication between neurons. There are many different kinds of seizures, and they can be grouped by where they occur in the brain, how much of the brain they affect, and the effect they produce externally. While we usually think of someone laying on the ground, shaking uncontrollably, seizures can look very different. For example, someone may stiffen like a board, or even stare absently into space.

The records we have seem to suggest that Caligula’s seizures were limited to his childhood. In fact, this makes sense. Childhood epilepsy is typically “grown out of” and is the form of epilepsy with the most evidence of genetic inheritance, explaining his family history. Most of these genetic risk factors are mutations in ion channels that bring charged particles in and out of neurons to maintain an appropriate electric charge. Disturbing ion transport can therefore lead to the changes in electrical activity that produce seizures. In addition, while Caligula may have eventually stopped having seizures, childhood epilepsy increases the risk for social impairments and mental illness later in life.

But what exactly caused Caligula’s abrupt personality change as an adult? Many theories have been proposed, but unfortunately, it’s hard to say for sure with the quality of sources available to us. However, the most notable detail we have is that Caligula became reckless, cruel, and egotistical after falling ill in October A.D. 37. According to the Ancient Roman historian Suetonius, who claimed that Caligula suffered from a "brain sickness", the emperor "was aware of [his] mental illness and at one time spoke of taking a break to recover from it" (Dando-Collins). Severe neuro-infection can induce a range of longer term neurological problems, one of them being encephalitis.

Encephalitis occurs when a virus infects the brain. The immune system is generally minimally active in the brain in order to prevent damage, but in the case of an infection, becomes activated, causing massive inflammation. We don’t really know what symptoms Caligula experienced when he was sick, but encephalitis usually presents with fever, visual impairments, headache, and seizures (note: we don’t know whether Caligula had any seizures as an adult). It is noted that it took him about a month to recover from his illness, which is consistent with the recovery period for encephalitis. But even after patients recover from encephalitis, the inflammation and damage caused by the immune system can cause a host of lasting changes, including personality changes, behavioral problems, loss of emotional control, impairments in planning and problem solving, and depression. So maybe a simple virus can explain how Caligula went from respected leader to a financially irresponsible, romantically reckless, self-aggrandizing totalitarian.

But maybe it had less to do with what was going on inside Caligula’s head and more to do with what surrounded him. Some scholars have looked at Caligula’s behavior through a different lens; that of the time period in which he lived. Ancient Rome wasn’t exactly the moral capital of the world, and it can be argued that Caligula’s behavior “displayed only in an exaggerated fashion the weaknesses of his time - prodigality, immorality, hedonism, cruelty and extravagance in all things” (Sandison). Thus, it’s possible that some of Caligula’s behavior that we interpret as a result of mental illness actually was just a reflection of his culture. Marrying and divorcing four women in a row, for example, illustrates the sexual attitudes of the time. Even the cruelty of the forced suicides he ordered were commonplace in ancient Rome. Caligula’s insistence that he be worshipped as a god could be explained by the great power he held and the widespread approval he got from his subjects. It has been suggested that his power to elevate others, like his sister, to the level of a deity, which past Roman leaders had done, led him to desire to be a god himself. Caligula certainly wouldn’t be the first leader in history to be corrupted by power.

This theory doesn’t explain all of Caligula’s behavior, but it’s important to consider the greater context. Even today we often are tempted to point to a mental or neurological illness to explain behavior in leaders that we don’t agree with. “Trump has narcissistic personality disorder.” “Biden has dementia.” It can be more uncomfortable to admit that someone just genuinely isn’t a good person. But simply explaining away their behavior by assuming they are mentally ill not only minimizes the need for personal responsibility, but also stigmatizes people who do have mental illness or neurological diseases. The vast majority don’t become vengeful womanizers. Caligula’s brain might explain the personality changes he experienced, but it’s not the full picture.

His reputation as the “maddest” emperor in history makes for a juicy narrative, but probably isn’t accurate. Caligula’s shortcomings as a man and ruler were likely multifactorial. The most likely explanation to me is that Caligula’s early life stress put him at increased risk for mental illness later on, and the onset was precipitated by an infection. His odd behavior was influenced by the culture of excess that he lived in.

The Significance

Following Caligula’s assassination, the people of Rome were distraught. When they heard the rumor that the murderers were loose in the city, citizens literally took up arms to avenge their emperor. When the military announced that Caligula’s Uncle Claudius would be his successor, they embraced him. After all, he was the brother of their beloved Germanicus and a member of the great Caesars. Immediately upon taking the throne, Claudius set out to erase any trace of his “mad” nephew, determined to validate his reign by making the people forget about the last four years with Caligula. He abolished the religious orders dedicated to worshipping the late emperor and his sister Julia Drusilla and cancelled or knocked down the many building projects Caligula had funded to cement his legacy. However, not all of Caligula’s impact could be erased.

Remember Caligula’s ill-fated British invasion attempt turned seashell collecting debacle? While Caligula and his army may not have executed on their plans for invasion, their mobilization did set the foundations for his Uncle Claudius to successfully invade Britain three years later. What had seemed like a manifestation of Caligula's instability actually prepared Claudius’ forces to readily mobilize and invade the highly coveted island. The Roman Empire’s attempts to conquer Britain would continue for many more decades, but under Claudius, the Roman army and its allies celebrated some significant wins. Claudius was honored with the military prestige that Caligula had longed for.

Caligula’s declaration of himself as a god also had far-reaching implications. Historically the relationship between the Jews and the Romans had been complicated, but they managed to coexist. Romans were content to allow the Jewish people to worship their God without interference, as long as they continued to show loyalty to their emperor. But after his dramatic change in personality and policy, Caligula was determined that the Jewish people would not be an exception to any of his new rules. The emperor’s carelessness when dealing with the potential revolt of millions of his citizens set off alarm bells among Caligula's peers who felt that his obsession with being worshipped was just one of the many indications that he was less of a leader and more of a tyrant.

The Senate also learned some valuable lessons from Caligula’s brief stint on the throne. Although he was not the first emperor, “he was the first Roman emperor in the full sense of the word, handed by a complacent senate almost unlimited powers over a vast section of the civilized world” (Barrett). Caligula was young when he came to power and had no leadership experience, having spent the majority of his young adult life under the debaucherous thumb of Tiberius and confined to the island of Capri. As emperor, he was (perhaps unintentionally) handed unlimited power and funds. Caligula ran roughshod over the same governing body of Rome that had provided past emperors with necessary checks and balances. Once he was assassinated, the senate wanted to “revert back to a republic” (Dando-Collins). This was why they murdered Caligula’s wife and child; to eliminate legitimate heirs that could pose a challenge to their plans. Ultimately the senate lost that battle to Claudius's supporters.

Someone who didn’t learn their lessons from Caligula’s rule? His sister Agrippina the Younger, who quickly got back to her scheming ways to pursue her lofty ambitions. It seems she was a little salty from the years she spent in exile after she was involved in a plot to overthrow her brother. In A.D. 48, Claudius had his wife executed for planning to overthrow him and the search began for a new wife. How convenient then that Agrippina should find herself newly single after her second husband had mysteriously died (it’s believed that she poisoned him). But wait, you say! Agrippina was Caligula’s sister, and Claudius was Caligula’s uncle. So, wouldn’t that make Claudius Agrippina’s uncle as well? Ding ding ding! Emperor Claudius received special permission to marry his niece Agrippina and subsequently adopted Agrippina’s son Nero.

Claudius also had a son, Britannicus, from one of his previous marriages. Agrippina had Britannicus poisoned, clearing the way for her son Nero to be named Claudius’s heir. Then, she supposedly had her uncle-husband poisoned as well. Nero would go on to become the only Roman emperor perhaps more infamous and cruel than his Uncle Caligula. He grew to resent his mother’s meddling and had her executed in A.D. 59. Whereas Caligula was hated predominantly by the upper echelons of society, Nero’s cruelty actually earned him the title “enemy of the people”. When it became clear that Nero would no longer be able to hold his throne, he took his own life, ending the nearly 100 year reign of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The Julio-Claudian dynasty was certainly a dynasty of firsts, both good and bad. Augustus was the first emperor of Rome. Caligula was the first emperor to be assassinated and his nephew Nero was the first emperor to commit suicide. Both Caligula and Nero are remembered two thousand years later for their exceptional cruelty and perceived madness. But it is the opinion of this particular historian that Caligula has been largely misrepresented throughout history. It is not as simple as saying “Caligula was a madman.” Everyone had high hopes for Caligula’s reign when he took the throne, including the young man himself.

Despite the fact that his short reign ended up going sideways, Caligula’s time on the throne was not a tragedy of the magnitude that his reputation would suggest. When Claudius was handed the throne after the death of his nephew, he inherited a strong Roman Empire. With all of the resources we have at our fingertips today, we must approach history with a discerning eye. Who are the sources and what was their relationship to the subject? Did they know the subject or are they writing with second-hand knowledge? Can any of the subject’s actions be understood in the context of the time period? Remember, what you see is not always what you get.

References

(n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/encephalitis/complications/

Barrett, Anthony A. Caligula: the Corruption of Power. Routledge, 2009.

Camargo, C. H., & Teive, H. A. (2018). Searching for neurological diseases in the Julio-Claudian dynasty of the Roman Empire. Arquivos De Neuro-Psiquiatria,76(1), 53-57. doi:10.1590/0004-282x20170174

Dando-Collins, Stephen. Caligula: the Mad Emperor of Rome. Ingram Pub Services, 2019.

DeBellis, M. D., & Zisk, A. (2014). The Biological Effects of Childhood Trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America,23(2), 185-222.

Epilepsy: Impact on the Life of the Child. (n.d.). Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.epilepsy.com/article/2014/3/epilepsy-impact-life-child

Marcomisano. “Ancient Rome and Judea: Caligula and the Temple of Jerusalem.” Jewish Rome Tours by Marco Misano (RomanJews), 21 Dec. 2019, www.romanjews.com/ancient-rome-and-judea-caligula-and-the-temple-of-jerusalem/.

Monroy, E., Hernández-Torres, E., & Flores, G. (2010). Maternal separation disrupts dendritic morphology of neurons in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens in male rat offspring. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy,40(2), 93-101. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2010.05.005

Remaly, J. (2019, June 17). Insomnia symptoms correlate with seizure frequency. Retrieved from https://www.mdedge.com/neurology/article/200717/epilepsy-seizures/insomnia-symptoms-correlate-seizure-frequency

Sandison, A. T. (1958). The Madness Of The Emperor Caligula. Medical History,2(3), 202-209. doi:10.1017/s0025727300023759

Sidwell, B. (2010). Gaius Caligula's mental illness. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20213971/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Caligula.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 27 Aug. 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Caligula-Roman-emperor.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Julia Agrippina.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1 Jan. 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Julia-Agrippina.

Toynbee, Arnold Joseph. “The First Triumvirate and the Conquest of Gaul.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1 Nov. 2019, www.britannica.com/biography/Julius-Caesar-Roman-ruler/The-first-triumvirate-and-the-conquest-of-Gaul.

Zhang, D., Liu, X., & Deng, X. (2017). Genetic basis of pediatric epilepsy syndromes. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine,13(5), 2129-2133. doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4267